2017, 2019, 2020, 2021: In the recent past, wine and fruit production has been affected by spring frost almost every year in France. Damages are very heterogeneous: They are sometimes localized as in 2019 in Normandy or in 2020 in the Rhone Valley, and sometimes they are severe and widespread as in 2017 and 2021.

The spring frost of 2021 was of particular concern because of its global impact, affecting almost all vineyards and fruit-growing plots in France (1)(2)(3). The 2021 frost event was also unusual because of the severe drop in temperatures that followed record high temperatures: In March 31, 2021, many temperature records were broken throughout France (26°C in Paris, 27.7°C in Cap Ferret, 26.3°C in Strasbourg …); followed by low temperature records on April 8, just as widespread (-5°C in Orleans, -4.3°C in Salon de Provence, -2.1°C in Montauban …). These temperatures had not been experienced since 1947! (4)

Thus, many professionals and institutions wonder about these temperature variations and recurrent frost event:

- Are we seeing an evolution in plant growth linked to climate change?

- What are the future trends in spring frost?

- Finally, how can we adapt to this evolution in the short, medium, and long term?

Are we seeing an evolution in plant growth linked to climate change?

Winter temperatures are increasing with climate change. These warmer winter temperatures impact the start of the crops growing season and the higher cumulative temperatures lead to a faster growth. Plant phenology, that is the timing of dormancy, budbursts, the emergence of leaves and flowers, first fruits, etc… is changing, and plants are reaching a growing stage that is sensitive to frost earlier in the season.

These phenological changes depend on crop types and climate change impacts at local level, but they lead to higher crop sensitivity to frost. Indeed, for a same calendar date and frost risk, crops are either more often in a sensitive stage of growth or in an even more sensitive stage than it was before. (To learn more on phenological stages and how it can help understand and reduce the impacts of climate change).

For example:

- -3°C on March 30th, occurring after a harsh winter when the buds remain closed, will have no consequences.

- -3°C on March 30th, occurring after a mild month of February and March when plants have young leaves or flowers, will do great damage.

Agronomic studies relying on several models such as STICS or BHV, have also demonstrated a strong link between temperature evolution and advancement of phenological stages, especially inviticulture (5). As climate models predict an increase in average temperature, bud burst dates will mechanically occur earlier, exposing viticulture and arboriculture to spring frosts earlier in the season.

For example, in Burgundy, the evolution of climate has already advanced the opening dates of vine buds by 7days between 1987 and now (6). A recent project on the impact of climate change and adaptation strategies on wine growing and wine production in France has also found that in Bordeaux bud breaks could occur nearly 1 day earlier every decade by 2100 (under the most pessimistic greenhouse gas emission scenario RCP8.5), about 2.5 days per decade in Colmar and up to 2.8 days for Avignon (LACCAVE (7)).

What are the future trends in spring frost?

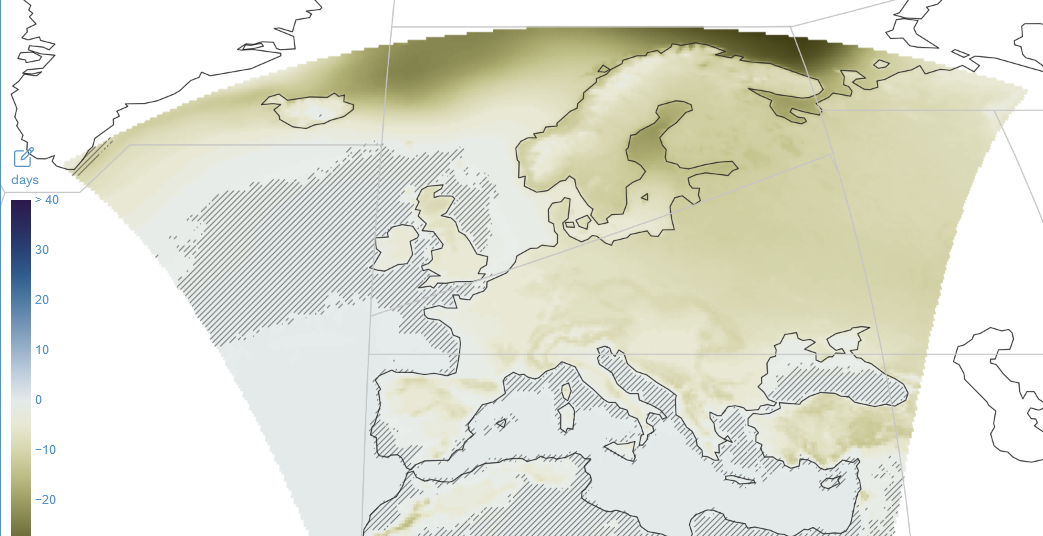

With global warming, the occurrence of freezing temperatures and cold spells are decreasing. The latest IPCC report (8) states that cold spells frequency will likely keep decreasing and virtually disappear towards the end of the century. In Europe, this decreasing trend is stronger over northern territories and high topography as displayed in the Figure below showing the decrease in the number of spring frost days by mid-century for the medium emission scenario (RCP 4.5).

Even though the number of frost days will be decreasing over Europe, the occurrence of cold spells in the spring will not disappear right away. Climate change is also linked to the weakening of the polar vortex, this area of low pressure and cold air around the pole. As explained in our previous article last year on Texas cold spell, this polar vortex weakening leads to a meandering polar jet stream that brings cold arctic air masses southwards.

Figure 1: Change in number of spring frost days in 2050 RCP4.5 relative to 1981-2010 (IPCC WGI Interactive Atlas: Regional information)

Business impact

Many types of crops can be impacted by these spring frost events. The fruit trees, grapes… can be impacted by a drop in production and also in quality. Following 2021 frost episode, French statistics organization (AGRESTE) indicates that on average for France (9) (10) (11):

- 60% production losses compared to the 2016-2020 average for apricots (a record for 46 years)

- 47% loss for peaches and 62% for cherries

- As for thevineyards, the damage is very variable depending on the localization of the domain. But some sectors suffered 70 to 100% losses

The adaptation measures

Knowing the risk of spring frost and its evolution, everyone can now develop a strategy for adaptation and evolution.

Short term solutions:

The question is about investing in protections against frost such as, among others, windmills, heating cables, candles or sprinkler systems. Such solutions require significant investments that would require good dimensioning of the tool and its limits, in particular regarding the future climate.

Concrete and materials answers could then be to plan for 300 candles/ha to protect up to -4°C and 500 candles to protect at -6°C; to perform Water spraying that can protect up to -7°C, but requires a large water reserve (12).

The limit of such a system is that it is very labor intensive and will have to be maintained and kept operational over the long term. Resources need to be operational around the clock to monitor and to timely trigger the system, e.g lighting up the candles at night.

The answer to spring frost therefore has to be multi-dimensional. Practical solutions shall come alongside upstream risk studies or downstream insurance. Financing solutions can then help to deploy the right set of preventive and defensive solutions.

In addition to these protection tools, more adaption practices can be implemented:

- Use of high vines (the cold air mass generally remains at ground level) (13)(14)

- Late pruning of the vine which, when done in February/March, allows to delay the date of budburst by about a week (15)

- Good reflexive adaptation after a frost, such as adapting the disbudding (16)

Medium term solutions:

In arboriculture as in viticulture, each graft/carrier pair has its own dynamics and its own resistance to hazards. Therefore, choosing the most adapted pair can allow the plant to resist the cold and to break out late.

However, this choice is complicated because the risk of frost is not the only one: It will also be necessary to face increased risks of strong heat and summer drought in summer, making even harder the choice of variety. This choice ends to cornelian when you include in the equation the legal framework – linked to the AOC – regarding the authorized grape varieties selection (17) (18).

Long term solutions:

In the long term, the challenge will probably go beyond spring frost and will more likely be about the global resilience of the sector against rise in temperatures and preponderant droughts.

Questions such as the relocation of wine productions from one region to another, most likely up North will have to be answered. It then brings the broader issue of the impact that change of terroir, varieties, and practices could have on wine quality.

Knowing the local climate and crops specificities through “suitability” studies allows to estimate the future relevance of each crop and to demonstrate the best adaptation measures to take locally in the coming decades.

It is possible today to anticipate the evolution of the organoleptic qualities of the products by studying the quality proxies linked to the climate (e.g. sugar/acidity rate). These results are then crossed with tests and surveys on consumer panels, to demonstrate the acceptability of these changes by customers (19). Merging these two types of studies creates a global approach to optimize the resilience of the sector.